Satiety Types: Why some people stay full longer & How to train your appetite

Did you know that your satiety phenotype might be the reason some people battle constant food cravings while others seem to stay effortlessly full?

Low Satiety Phenotype (LSP) individuals tend to crave high-fat foods, snack more, and struggle with weight loss, while High Satiety Phenotype (HSP) individuals naturally eat less and feel satisfied faster ¹ ².

Sounds unfair, right? But don’t worry! You might be able to do something about it. And that’s exactly what we’ll explore in this article!

Understanding your appetite: Are you an LSP (Low Satiety Phenotype)

Do you ever feel like you’re always hungry, even after eating?

Some people naturally struggle with appetite control, making it harder to recognize when they're truly full. Some studies suggest that a weaker satiety response, where your body doesn’t send strong “I’m full” signals can make you more prone to overeating and weight gain ¹ ³.

If you often find yourself eating beyond fullness or constantly craving snacks, you might be one of them.

Hunger, Satiety, and Satiation and Appetite

Satiety versus Satiation

Many people use the terms hunger, appetite, satiety, and satiation interchangeably, but they are not the same thing, even though they are closely linked.

Hunger vs. Appetite: They Are Not the Same Thing

Hunger is a biological need for food, your body’s way of signaling that it needs energy (e.g., stomach growling).

Appetite* is a desire to eat, which can be triggered by sight, smell, or other external cues, even if you’re not physically hungry. For example, eating just because food is available, craving food after scrolling through food content on TikTok (even if you just ate), or passing by McDonald’s and suddenly wanting fries.

*Appetite can arise from hunger, but more often, it is triggered by emotional or environmental factors⁴.

Satiety vs. Satiation: They Are Not the Same Thing Either

Satiation is the feeling of fullness during a meal, telling you to stop eating.

Satiety is how long you stay full after eating, influencing how many hours pass before your next meal⁵.

So, why are satiety and satiation important? They can influence how much people eat, which affects weight and obesity risk ⁶.

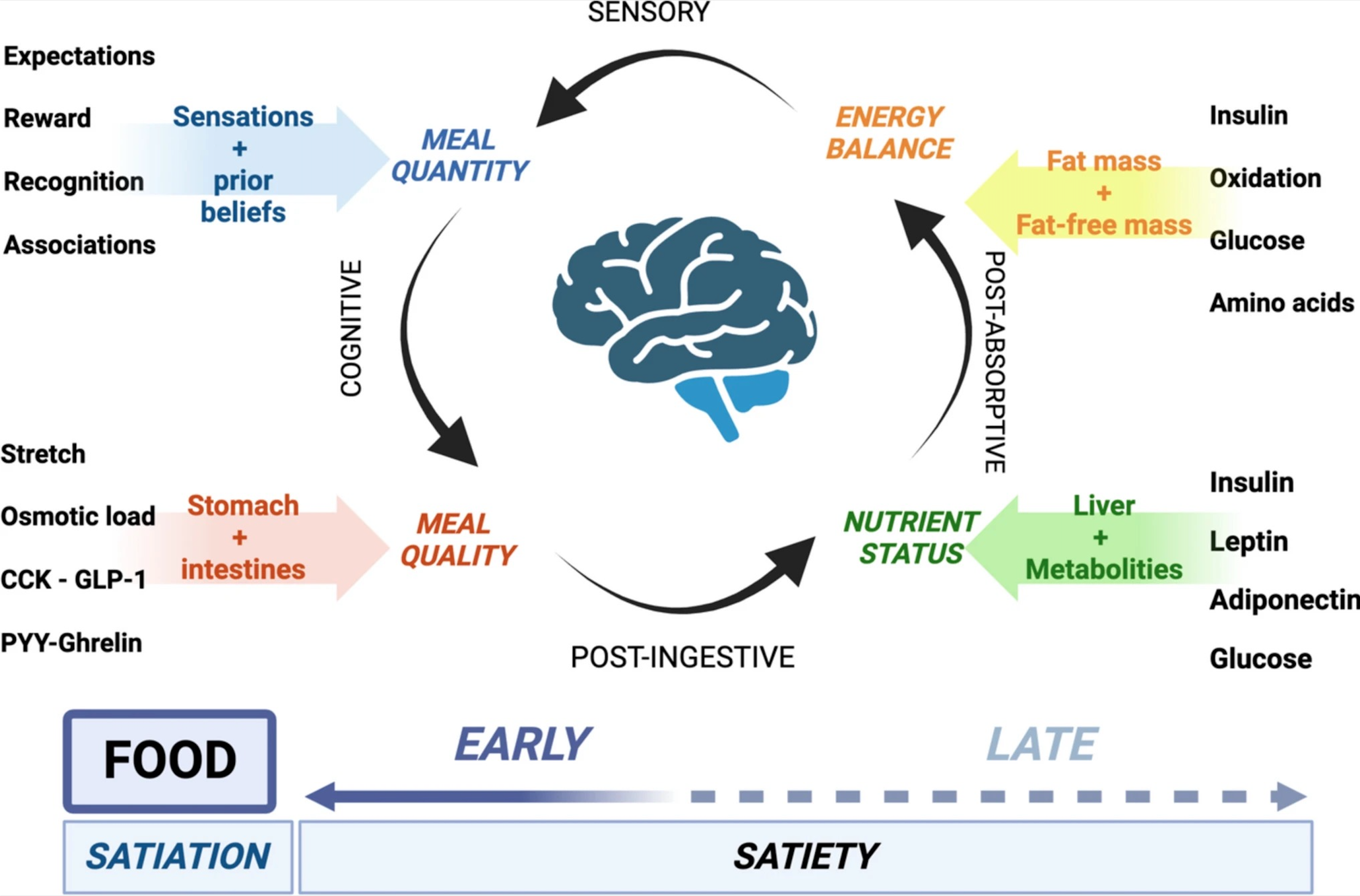

What determines satiety and satiation? Well…It’s not that simple. Many factors come into play. Satiety isn’t just about food. See Fig. 1, ‘The Satiety Cascade’, for a breakdown.

Satiety Cascade, from (Garutti et al.)

Now, what actually controls your hunger?

Again, it's not that simple... You might have eaten a perfectly balanced meal with the right amount of calories and nutrients, but if you walk past your favorite bakery, you might suddenly crave a croissant or pain au chocolat. This happens because sensory cues can trigger hunger, even when your body doesn’t actually need food⁶.

Factors influencing food intake, satiation, and satiety: biological, physiological, psychological, and environmental factors.

Hunger and fullness are shaped by physiological signals (like macronutrient composition and energy needs), psychological factors (such as stress, cravings, and learned behaviors), and environmental influences (including food availability, culture, and marketing). Biological factors like gut hormones and neurotransmitters also play a key role in regulating appetite.

And this is why managing weight isn’t as simple as just “eating less” !

How to enhance Satiety and Appetite Control if you have a low satiety phenotype (LSP)

I won’t dive too deep into the details (because nobody wants another ridiculously long article, which I'm notorious for), but here are the key strategies you should focus on:

1. Eat more high-satiety, low-calorie foods

Note: The Satiety Index ⁸* scores are percentages relative to white bread, which has a baseline score of 100%. The calorie values are approximate and can vary based on preparation methods and specific varieties.

And no, I don’t mean just piling your plate with lettuce and spinach: that might keep you full for an hour, but then what? The key is to include all macronutrients for long-lasting fullness:

✅ Protein: egg whites, tofu, textured soya, lentils, beans, Greek yogurt, lean chicken, turkey, and white fish.

✅ Fiber-Rich Carbs: oats, lentils, beans and lentils, and non-starchy vegetables.

✅ Healthy Fats (but in small amounts): avocados, nuts, chia seeds, and flaxseeds.

Big disclaimer: The Satiety Index is based on a limited number of foods tested in a single study (Holt et al., 1995). While these foods ranked highest in satiety, everyone's body responds differently to different foods. Your personal satiety foods might differ depending on meal composition, macronutrient balance, and individual metabolism. But you can use this list as a starting point.

Also it would be interesting to see this study recreated with a wider variety of foods, especially more vegetables, different protein sources, and mixed meals to get a fuller picture of satiety promoting foods.

2. Get ‘‘maximum fullness’’ per calorie

For the most satiety per bite, focus on lean proteins, non-starchy veggies, slow releasing carbs, and high-fiber fruits. Boiled potatoes, egg whites, chicken breast, white fish, turkey, and low-fat Greek yogurt rank highest in satiety-per-calorie ratios: so these should be your go-to foods.

Protein is the king of macronutrients, protein has the strong impact on satiety, satiation, appetite and hunger.

Protein is, for me, the king of macronutrients (except when I’m training for a marathon, then carbs take its place). And for good reason: eating enough protein comes with sooo many benefits!

Keeps you full longer: protein is the most filling macronutrient, meaning it helps control hunger better than carbs or fat, which can naturally reduce how much you eat⁹.

More calories burned: your body burns more calories digesting protein (thermic effect of food) than other nutrients⁹.

Supports muscle and metabolism: protein helps maintain or build lean muscle, which is important for strength, metabolism, and overall health⁹.

Your brain recognizes protein as filling: just seeing or smelling protein-rich foods can make you expect them to be more satisfying, making high-protein meals a smart choice for controlling hunger ¹⁰.

Helps with weight loss and maintenance: studies show that a higher-protein diet not only helps with weight loss but also prevents weight regain. It helps you burn fat while preserving your muscle, supports appetite-regulating hormones, and increases calorie burn through TEF¹¹.

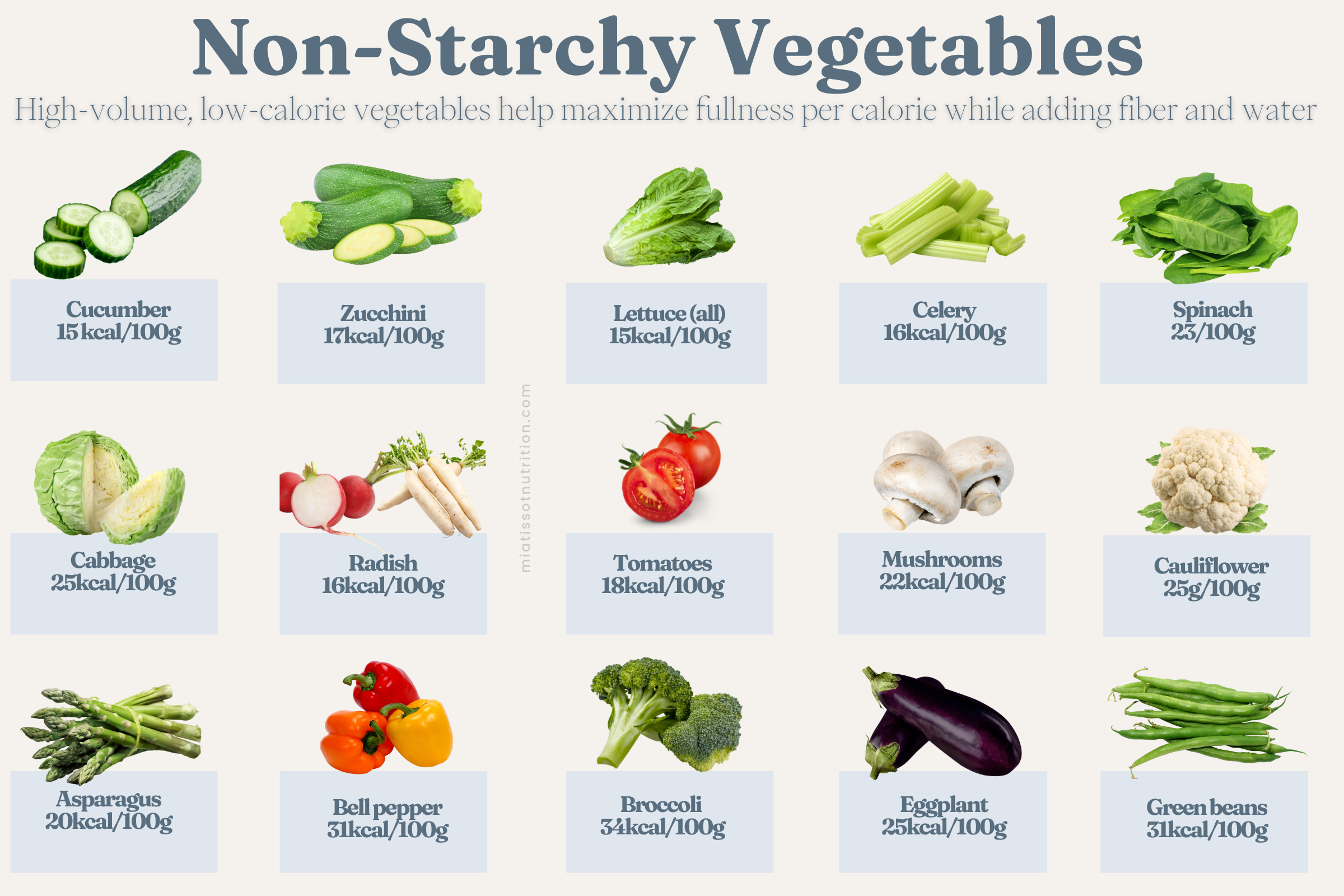

High-volume, non-starchy vegetables help keep you full, support gut health, and stabilize blood sugar levels.

I can’t believe fruits and vegetables are demonized by some people when consistent research shows they are incredibly beneficial.

There are epidemiologists who have dedicated their entire careers to studying this! I get it, some people have an issue with ‘‘Big Pharma’’, but what’s the problem with fruits and vegetables? Fruits and vegetables aren’t even that profitable compared to sugary, ultra-processed foods…

Anyway, not all vegetables have the same impact on weight and appetite. Research consistently shows that eating more non-starchy, high-fiber vegetables is linked to better weight management and increased satiety.

Fiber-rich vegetables help regulate appetite by slowing digestion, promoting fullness, and influencing hunger-related hormones. They also have a lower glycemic load and feed your gut bacteria. Studies show that higher fiber intake is linked to lower calorie consumption over time, and replacing refined grains, sugary foods, and starchy vegetables with non-starchy vegetables helps reduce overall calorie intake and prevent weight regain¹² ¹³ ¹⁴ ¹⁵.

High-Fiber Carbs: Fiber slows digestion, helps with stable blood sugar manangement and supports satiety, satiation, appetite and hunger.

3. Eat more calories earlier in the day

Don’t knock it till you try it! Studies (like The Big Breakfast Study¹⁶) show that eating a larger breakfast helps regulate appetite throughout the day. People who front-load their calories in the morning tend to experience less hunger and better satiety control compared to those who eat their biggest meal at night.

I wasn’t a big fan of breakfast until I noticed its impact on my overall appetite throughout the day. Also, not sure if it’s related, but my daily energy crash and sluggishness around 4 PM disappeared.

4. Try Preloading your meals

In other words, preloading is like having an appetizer: except you choose a healthy version.

So, you eat or drink something small and nutrient-dense (like a salad, soup, or protein shake) before your main meal to help control appetite and prevent overeating. Research shows that preloading with protein, fiber, or even just water can increase satiety, regulate blood sugar, and support weight management ¹⁷ ¹⁸ ¹⁹ ²⁰ ²¹ .

5. Watch out for hidden appetite disruptors: Sleep, Stress & Alcohol

Lack of sleep, chronic stress, and alcohol can create appetite dysregulation ²² ²³ ²⁴, making hunger hormones like ghrelin more active while satiety hormones (such as leptin and GLP-1) decline.

6. Set up your environment for appetite success

If you keep hyper-palatable food easily accessible, you'll eat it; not because you're hungry, but because it's there. If you have strong willpower or don't have an issue with this, ignore this.

Stock your fridge with healthy options (lean proteins, high-fiber carbohydrates, fruits, and vegetables).

Make unhealthy foods harder to access. If having pizza, ice cream, etc., in the house makes you eat it daily, consider only buying it when you truly crave it.

Another annoying disclaimer:

I know not everyone will agree with this because some argue that restricting foods makes cravings worse, which can be true for some people. But I am not saying you should never eat pizza again. What I am saying is to be intentional about it. If you crave pizza, go buy it when you truly want it or plan for it. For example, "This Monday, I’m having pizza."

You also need to identify your personal trigger foods, the ones you tend to overeat. For some, it’s pizza, for others, it’s ice cream or chocolate. Personally, I have no issue with chocolate. I even brought some from South America that has been sitting untouched for three months. Ice cream is the same. I can have it in the freezer for weeks without caring.

But crisps? That’s somethingelse for me. That’s why I stopped buying big bags and instead get small, single-serving packs (30-40g) so I can enjoy them without accidentally overeating.

7. Don’t wait until you’re starving: your cravings will win!

Don’t fool yourself into thinking your willpower is stronger than millions of years of evolution… You might believe that skipping meals will save you calories, but waiting until you're ravenous triggers physiological responses that work against your goals.

Going too long without eating can cause blood sugar drops, leading to tiredness, irritability, trouble concentrating (loads of food noise), and intense cravings for quick energy. When that happens, it becomes much harder to make rational food choices and you’re more likely to grab whatever is available and eat it quickly, without considering its nutritional value.

What to do instead:

Eat regular meals and snacks.

A mild hunger level is normal while dieting, but avoiding extreme hunger prevents overeating.

8. Some foods will trigger hedonic eating

The high fat + high refined carb (sugar) combo creates the ultimate pleasure-eating experience. Ever wonder why foods like pizza, ice cream, croissants, and fries are so much harder to stop eating than, say, chicken and rice?

That’s because foods high in both carbs and fats trigger powerful pleasure signals in the brain ²⁶ (brain’s dopamine reward system, the same pathway involved in addictive behaviors), making them extra tempting.

Do what you want with this information…I’m not here to be the mean nutritionist who demonizes hyperpalatable foods.

9. Reduce opportunistic eating (change your environment)

I touched a bit on this earlier but I decided to be back at it because I think people underestimate the importance of this aspect. So what is opportunistic eating?

Opportunistic eating is eating just because food is available²⁵, rather than because you’re hungry. It’s often triggered by sight, smell, or social situations.

Why does it happen?

Our brains are wired to seek food (a survival instinct).

Highly processed, palatable foods (like chips or sweets) override natural satiety cues.

Social settings and habits encourage mindless snacking.

How to manage it?

Ask yourself ‘Am I actually hungry, or just eating because it’s there?’

Out of sight = out of mind, keep tempting foods away (or swap them for healthier options).

Have structured meal times to reduce random snacking.

Appetite is largely learned (Even if you don’t realize it)

You might think your cravings are just part of who you are, but in reality, a lot of your appetite is learned ²⁷.

Your brain forms habits around food without you even noticing. That’s why you suddenly need something sweet after dinner or automatically grab snacks while watching Netflix. Let’s break it down:

1.Classical Conditioning (Pavlovian Learning

Noticed how you always crave crisps/icecream/whatever when watching Netflix or TV? That’s because your brain has paired Netflix (cue) with crisps (reward). Now, one triggers the other, even if you’re not actually hungry ²⁸.

I associated Netflix = eating popcorn and it took me a long time to break this habit, but now I have no issues with it anymore.

2.The habit loop

Cue (Netflix or TV) → behavior (eating icecream) → reward (pleasure).

The more you repeat it, the stronger the habit gets.

3.Automatic Eating / Environmental Cue Eating

A lot of eating happens simply because the environment triggers it, not because you’re actually hungry. The smell of fresh pastries, seeing someone eat, or just being in the habit of snacking in front of the TV can override real hunger signals.

The good news? You can unlearn it.

No, it’s not going to be easy, and I am telling you this from my own experience. If you want to break the cycle, start by changing the cue (e.g., swap icecream for high protein yogurt) or disrupting the routine.

Be mindful and ask yourself, “Am I actually hungry, or is this just a habit?”

If you can’t give it up completely, create new associations. Train yourself to crave healthier versions of the foods you enjoy.

Final thoughts

Different foods impact satiety, satiation, appetite, and hunger in different ways: especially if you have a Low Satiety Phenotype (LSP).

Some foods are even engineered to be hyper-palatable and easy to overeat, and this applies to everyone, not just those with an LSP. But that doesn’t mean you can never enjoy your favorite cake again! There’s no need to go down the unnecessary restriction route.

AAAAAnd that’s it! If you’ve made it this far, I’m impressed, and I hope you found this useful.

P.S. If you need a nutritionist to help you lose weight (minus the hunger and food noise), I’d love to help!

I look forward to helping you thrive!

M.

Curious to learn more ? Check out other articles on the blog for tips, myths, and science-backed insights:

References (to geek out further):

1.Dalton, Michelle, et al. “Weak Satiety Responsiveness Is a Reliable Trait Associated with Hedonic Risk Factors for Overeating among Women.” Nutrients, vol. 7, no. 9, 4 Sept. 2015, pp. 7421–7436, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu7095345.

2.Buckland, Nicola J., et al. “Women with a Low-Satiety Phenotype Show Impaired Appetite Control and Greater Resistance to Weight Loss.” British Journal of Nutrition, vol. 122, no. 8, 24 July 2019, pp. 951–959, https://doi.org/10.1017/s000711451900179x.

3.Drapeau, V., et al. “Behavioural and Metabolic Characterisation of the Low Satiety Phenotype.” Appetite, vol. 70, Nov. 2013, pp. 67–72, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2013.05.022.

4.Brunner, Eric J., et al. “Appetite Disinhibition rather than Hunger Explains Genetic Effects on Adult BMI Trajectory.” International Journal of Obesity, vol. 45, no. 4, 14 Jan. 2021, pp. 758–765, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-020-00735-9.

5.Bellisle, France, et al. “Sweetness, Satiation, and Satiety.” The Journal of Nutrition, vol. 142, no. 6, 1 June 2012, pp. 1149S1154S, academic.oup.com/jn/article/142/6/1149S/4689069, https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.111.149583.

6.Ni, Dongdong, et al. “Integrating Effects of Human Physiology, Psychology, and Individual Variations on Satiety–an Exploratory Study.” Frontiers in Nutrition, vol. 9, 27 Apr. 2022, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.872169.

7.Garutti, Mattia, et al. “Hallmarks of Appetite: A Comprehensive Review of Hunger, Appetite, Satiation, and Satiety.” Current Obesity Reports, vol. 14, no. 1, 24 Jan. 2025, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-024-00604-w.

8.Holt, S. H., Miller, J. C., Petocz, P., & Farmakalidis, E. (1995). A satiety index of common foods. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 49(9), 675-690.

9.Paddon-Jones, Douglas, et al. “Protein, Weight Management, and Satiety.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, vol. 87, no. 5, 1 May 2008, pp. 1558S1561S, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/87.5.1558s.

10.Morell, P., and S. Fiszman. “Revisiting the Role of Protein-Induced Satiation and Satiety.” Food Hydrocolloids, vol. 68, no. 68, July 2017, pp. 199–210, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2016.08.003.

11.Moon, Jaecheol, and Gwanpyo Koh. “Clinical Evidence and Mechanisms of High-Protein Diet-Induced Weight Loss.” Journal of Obesity & Metabolic Syndrome, vol. 29, no. 3, 30 Sept. 2020, pp. 166–173, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7539343/, https://doi.org/10.7570/jomes20028.

12.Wan, Yi, et al. “Association between Changes in Carbohydrate Intake and Long Term Weight Changes: Prospective Cohort Study.” BMJ, vol. 382, 27 Sept. 2023, p. e073939, www.bmj.com/content/382/bmj-2022-073939, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2022-073939.

13.Li, Yingrui, et al. “Associations of Starchy and Non-Starchy Vegetables with Risk of Metabolic Syndrome: Evidence from the NHANES 1999–2018.” Nutrition & Metabolism, vol. 20, no. 1, 31 Aug. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12986-023-00760-1.

14.Nour, Monica, et al. “The Relationship between Vegetable Intake and Weight Outcomes: A Systematic Review of Cohort Studies.” Nutrients, vol. 10, no. 11, 2 Nov. 2018, p. 1626, www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/10/11/1626/htm, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10111626.

15.Bertoia, Monica L., et al. “Changes in Intake of Fruits and Vegetables and Weight Change in United States Men and Women Followed for up to 24 Years: Analysis from Three Prospective Cohort Studies.” PLOS Medicine, vol. 12, no. 9, 22 Sept. 2015, p. e1001878, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26394033/, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001878.

16.Ruddick-Collins, L. C., et al. “The Big Breakfast Study: Chrono-Nutrition Influence on Energy Expenditure and Bodyweight.” Nutrition Bulletin, vol. 43, no. 2, 8 May 2018, pp. 174–183, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5969247/pdf/NBU-43-174.pdf, https://doi.org/10.1111/nbu.12323.

17.Ortinau, Laura C, et al. “Effects of High-Protein vs. High- Fat Snacks on Appetite Control, Satiety, and Eating Initiation in Healthy Women.” Nutrition Journal, vol. 13, no. 1, 29 Sept. 2014, https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-13-97.

18.Glynn, Erin L, et al. “Consuming a Protein and Fiber-Based Supplement Preload Promotes Weight Loss and Alters Metabolic Markers in Overweight Adults in a 12-Week, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial.” The Journal of Nutrition, 25 Feb. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/nxac038.

19.Akhavan, Tina, et al. “Mechanism of Action of Pre-Meal Consumption of Whey Protein on Glycemic Control in Young Adults.” The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry, vol. 25, no. 1, Jan. 2014, pp. 36–43, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnutbio.2013.08.012.

20.Astbury, Nerys M, et al. Dose–Response Effect of a Whey Protein Preload on Within-Day Energy Intake in Lean Subjects. Vol. 104, no. 12, 28 Sept. 2010, pp. 1858–1867, https://doi.org/10.1017/s000711451000293x.

21.Jeong, Ji Na. “Effect of Pre-Meal Water Consumption on Energy Intake and Satiety in Non-Obese Young Adults.” Clinical Nutrition Research, vol. 7, no. 4, 2018, p. 291, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6209729/, https://doi.org/10.7762/cnr.2018.7.4.291.

22.Liu, Shuailing, et al. “Sleep Deprivation and Central Appetite Regulation.” Nutrients, vol. 14, no. 24, 7 Dec. 2022, p. 5196, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14245196.

23.Hill, Deborah, et al. “STRESS and EATING BEHAVIOURS in HEALTHY ADULTS: A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW and META-ANALYSIS.” Health Psychology Review, vol. 16, no. 2, 29 Apr. 2021, pp. 1–87, https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2021.1923406.

24.Kwok, Alastair, et al. “Effect of Alcohol Consumption on Food Energy Intake: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” British Journal of Nutrition, vol. 121, no. 5, 1 Mar. 2019, pp. 481–495, www.cambridge.org/core/journals/british-journal-of-nutrition/article/effect-of-alcohol-consumption-on-food-energy-intake-a-systematic-review-and-metaanalysis/2F9AB5C64A86329EB9E817ADAEC3D88C, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114518003677.

25.Fay, Stephanie H., et al. “Psychological Predictors of Opportunistic Snacking in the Absence of Hunger.” Eating Behaviors, vol. 18, Aug. 2015, pp. 156–159, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1471015315000677, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2015.05.014.

26.Volkow, Nora D., et al. “Reward, Dopamine and the Control of Food Intake: Implications for Obesity.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences, vol. 15, no. 1, Jan. 2011, pp. 37–46, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3124340/, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2010.11.001.

27.Blundell, J., et al. “Appetite Control: Methodological Aspects of the Evaluation of Foods.” Obesity Reviews, vol. 11, no. 3, Mar. 2010, pp. 251–270, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3609405/, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789x.2010.00714.x.

28.Bongers, Peggy, and Anita Jansen. “Emotional Eating and Pavlovian Learning: Evidence for Conditioned Appetitive Responding to Negative Emotional States.” Cognition and Emotion, vol. 31, no. 2, 5 Nov. 2015, pp. 284–297, https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2015.1108903.